by Hannah Smith, IMHM Graduate Intern

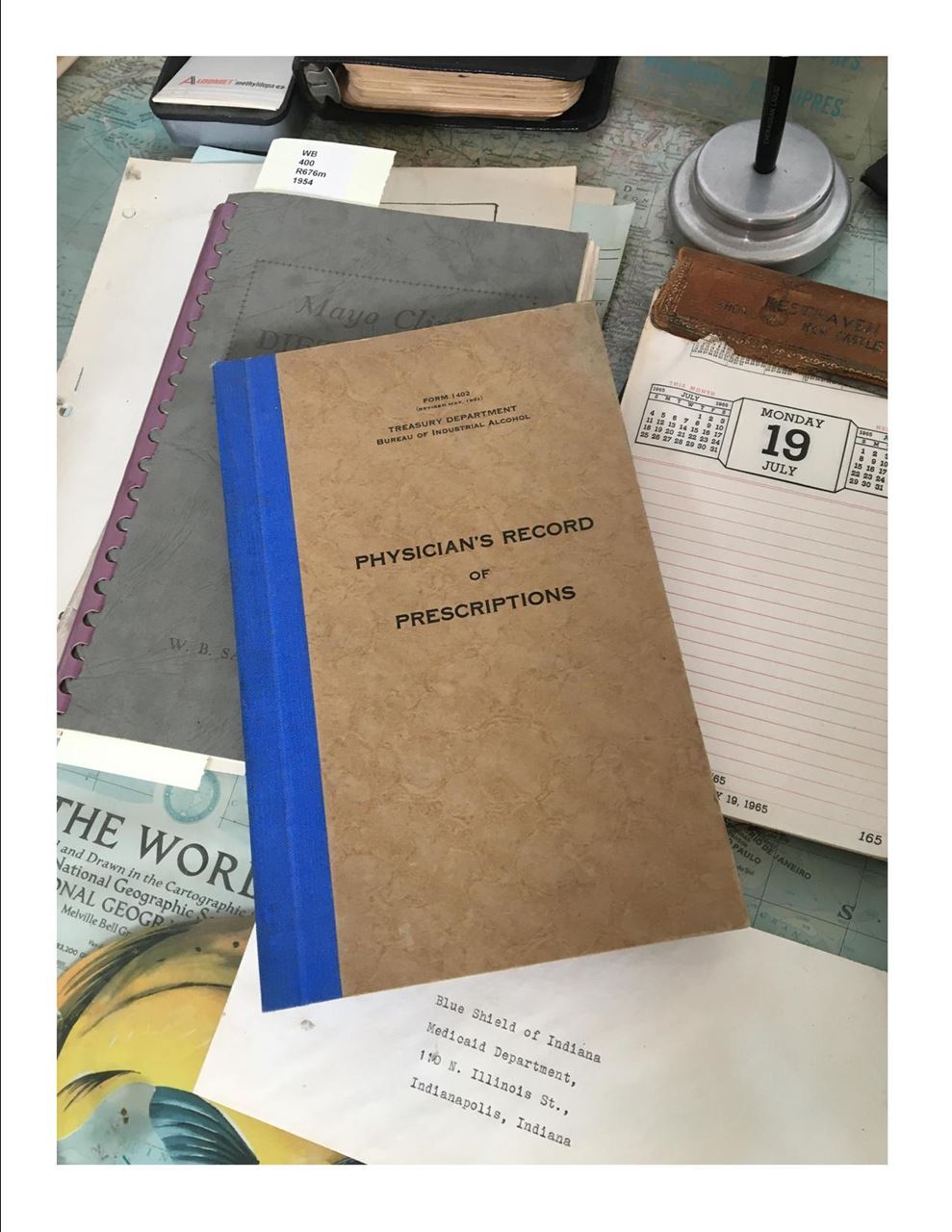

Currently, across the blooming medicinal plant garden, in the small brick building that used to be the Dead House, are the entire contents of Dr. Marion Scheetz’s home office. Dr. Scheetz graduated from medical school in the early 1930s and went on to become a general practitioner and country doctor out of Lewisville, Indiana. The contents of his office include an x-ray viewer, surgical and medical books, an exam bed, and his desk. Among other things on his desk – like a mid-century stethoscope – there lies a thin book with blue binding titled Physician’s Record of Prescriptions. The book is courtesy of the American Medical Spirits Company and provides instructions and regulations for prescribing patients alcohol for medicinal purposes during Prohibition.

Currently, across the blooming medicinal plant garden, in the small brick building that used to be the Dead House, are the entire contents of Dr. Marion Scheetz’s home office. Dr. Scheetz graduated from medical school in the early 1930s and went on to become a general practitioner and country doctor out of Lewisville, Indiana. The contents of his office include an x-ray viewer, surgical and medical books, an exam bed, and his desk. Among other things on his desk – like a mid-century stethoscope – there lies a thin book with blue binding titled Physician’s Record of Prescriptions. The book is courtesy of the American Medical Spirits Company and provides instructions and regulations for prescribing patients alcohol for medicinal purposes during Prohibition.

The era of Prohibition (1920-1933) typically brings about images of speakeasies, bootleggers, and mobsters, but there was another way to get your hands on a pint of whiskey (or rum, vodka, gin, brandy, beer or wine): through your friendly neighborhood physician. When Congress signed the Volstead Act – the law that enforced the 18th Amendment – it allowed any physician “holding a permit to prescribe liquor” after a “careful physical examination” of the patient.[1] Curiously, Congress added this section despite the American Medical Association’s (AMA) dismissal of “therapeutic” or medicinal value of alcohol. The AMA may have discouraged the use of alcohol to treat illness, but doctors across the country prescribed more alcohol than ever before during Prohibition.[2]

Indeed, because of loopholes in the laws and regulations, physicians found financial gain in the business of prescribing alcohol during Prohibition. Americans paid $3 – the equivalent of almost $50 today – for a prescription, and another $3 or $4 to fill them.[3] For some physicians, who both wrote and administered prescriptions, that was money in their pockets. While the law required doctors all across the country to mark down justifications for prescriptions, some doctors found loopholes for prescribing alcohol such as simply writing “debility.”[4] And according to Physician’s Record of Prescriptions, “emergency prescriptions” could be administered for “the saving of human life, the amelioration of great pain, or where delay would aggravate a serious ailment.”[5] Not only could doctors prescribe alcohol for ambiguous reasons, patients could also gain access to it quickly.

Ultimately, in 1933, Prohibition came to an end. It was clear to lawmakers and the public that the 18th Amendment was a failure. Organized crime related to bootlegging increased, but also the federal government needed the tax revenue from liquor sales during the Great Depression.[6] The ratification of the 21st Amendment meant no more lucrative prescriptions for physicians (at least for alcohol), but it did not mean Americans ceased self-medication with booze. In fact, one of the most significant and long-lasting unintended consequences of Prohibition was that more Americans were drinking alcohol, and drinking in larger quantities.[7]

Hannah Smith is a first-year Public History MA student at IUPUI and graduate intern at the Indiana Medical History Museum. She enjoys working with archives and collections, writing, and reading books of all kinds.

[1] Volstead Act, Sixty-Sixth Congress, Sess. I, CHS. 81, 82, 85 (1919), https://www.loc.gov/law/help/statutes-at-large/66th-congress/session-1/c66s1ch85.pdf.

[2] Jennie Cohen, “Drink Some Whiskey, Call in the Morning: Doctors & Prohibition,” History (original: 17 January 2012; updated: 29 August 2018), https://www.history.com/news/drink-some-whiskey-call-in-the-morning-doctors-prohibition.

[3] Paula Mejia, “The Lucrative Business of Prescribing Booze During Prohibition: Those looking to self-medicate could score at the doctor’s office,” Atlas Obscura (15 November 2017), https://www.atlasobscura.com/articles/doctors-booze-notes-prohibition; CPI Inflation Calculator, Bureau of Labor Statistics, accessed 22 April 2020, https://data.bls.gov/cgi-bin/cpicalc.pl.

[4] Mejia.

[5] Physician’s Record of Prescriptions, form 1402, Treasury Department: Bureau of Industrial Alcohol, The American Medical Spirits Company (Louisville, KY: revised May 1931).

[6] Christopher Klein, “The Night Prohibition Ended: Look back at America’s surprising reaction to the end of Prohibition,” History (original: 5 December 2013; updated: 10 December 2018), https://www.history.com/news/the-night-prohibition-ended.

[7] Michael Lerner, “Unintended Consequences,” PBS,Prohibition: A film by Ken Burns and Lynn Novick, https://www.pbs.org/kenburns/prohibition/unintended-consequences/.