by Norma Erickson

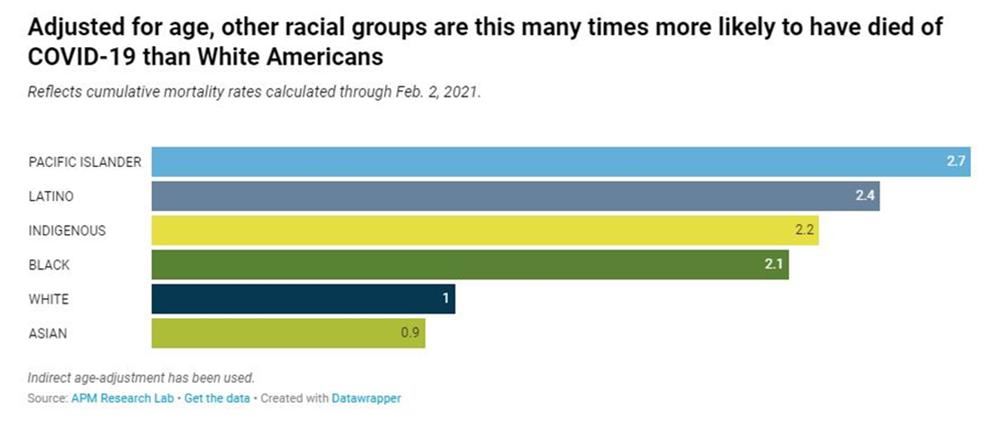

The COVID-19 pandemic has revealed many cracks in the American healthcare system. Healthcare disparity for racial and ethnic groups is just one of the problems that is standing in the way of battling this disease. Pacific Islanders, Latino, Black and Indigenous Americans all have a COVID-19 death rate of double or more than that of White and Asian Americans. Multiple factors contribute to this increase and someone who is not a person of color might have a problem understanding this.

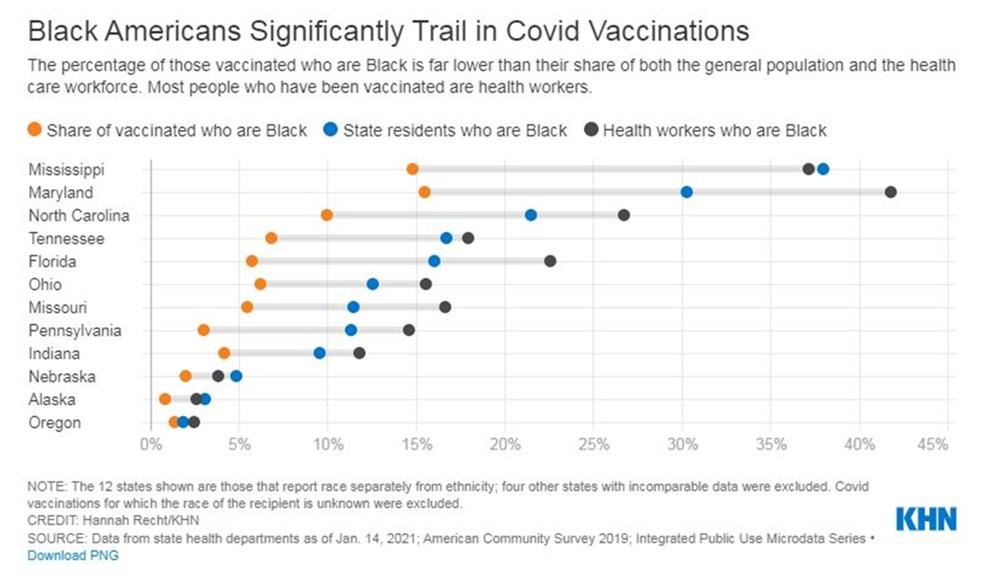

For African Americans, the specter of mistrust is one barrier that must be addressed in the current health crisis. Sometimes such doubt is attributed to skepticism about new technologies. Perhaps deeper, memories of disrespect and mistreatment by the healthcare system still linger, as current examples make their way to the news and reinforce that belief. These fears are leading to vaccine hesitancy among Black Americans. To address these fears and feelings, you must exhume and examine their origins.

Time and time again, one particular incident is spotlighted as an example of how African Americans were mistreated and abused by a public health organization, leading to mistrust of the healthcare system. The Tuskegee Study of Untreated Syphilis in the African American Male was certainly one of the most orchestrated, egregious medical assaults against Black men, allowing some study subjects to live uncured when a viable treatment was available. But some might agree and say—“that was not a good thing, but what does that have to do with here and now? After all, that happened in Tuskegee, Alabama; it didn't happen here.” Au contraire. Wherever your “here” may be, tragedies likely occurred, but not on the scale of the Tuskegee study. They certainly did happen in Indianapolis’ history.

In the first decade of the 20th century, physicians Indianapolis’ Black community surrendered to the fact that they were not going to be granted privileges to treat their patients in the municipal City Hospital and those patients who were admitted would not be well-treated. They decided to establish their own clinics and hospitals to offer safe, dignified care. A few years prior to this, there were two incidents which were very much in the public eye that demonstrated the Black community’s belief that their lives would always be in peril if they had to enter the hospital.

In November of 1904, two student nurses mistook a pitcher that contained a strong disinfectant for a jug of warm water that had been prepared for patient use. Their error resulted in two women receiving deadly carbolic acid enemas. One patient was White, the other Black; the incident was an example of the questionable safety of hospitalization for both communities because City Hospital was a training ground for both student doctors and nurses. Since City Hospital was the only such facility in Indianapolis that admitted them, Black patients would always be at risk of being “clinical material” for trainees. Often, this is still the case in teaching hospitals. Many institutional policies protect the patient now—but can they be trusted?

In March of 1905, Nurse Mary Mayes of the Flower Mission Hospital, a new tuberculosis facility on the grounds of the City Hospital, visited the home of Thomas Jones, a seriously ill African American man with a wife and child. Two Black physicians recently examined Jones and one wrote an order for him to be admitted to City Hospital. A neighbor, for unknown reasons, took the note to the Flower Mission Hospital instead of City Hospital. Mrs. Mayes conducted a routine home visit to determine eligibility, but she called the City Hospital to send an ambulance to transport the very sick man there—not to the TB hospital. Since tuberculosis cases were prohibited from City Hospital, Mayes apparently did not think Jones was suffering from the disease. Eventually, his temperature reached 103 degrees and he began to bleed from his nose. When the City ambulance did not arrive, Mayes asked C.M. Willis, a Black undertaker, to take the man and his wife to the hospital in his carriage. Before Jones left her care, Mayes collected a sputum specimen to send to a lab for testing. When they arrived at the hospital, the doctor on duty, an intern, looked at the man—still in the carriage—and saw blood on the front of his clothes. He immediately assumed the patient was coughing up blood because he had tuberculosis. The doctor did not did take Jones’s temperature nor remove the patient to an examination room. Willis was then told to take the ill man to the county poor house. He did so and thirty minutes later, Thomas Jones died.

This event caused an uproar in the Black community, but it was not unknown by the rest of Indianapolis. Reports of this case occupied the pages of the Indianapolis Star and the Indianapolis News for three weeks. Why was the patient turned away? Did the patient really have tuberculosis? Who was ultimately to blame for refusing to treat him? This story might never have made it to the press if the hospital was not already under scrutiny for the other horrific incident that happened just a few months prior.

There were few immediate results of these tragic events. The nurses were exonerated for being overworked and the doctor on duty received a ten-day suspension for not following policy. What of Mr. Jones’s laboratory tests? Both ante mortem and postmortem samples were negative for tuberculosis bacilli.

These appalling incidents explain why City Hospital’s poor standard of care—by both physicians and nurses—advanced the Black community’s decision to establish their own hospitals. Besides the mistrust of medical treatment, there was also fiscal mistrust. There were decades of unfulfilled promises by politicians and White doctors. One major struggle involved the 1939 accusations by Black citizens that the city had received $157,000 from the Federal Public Works Administration to build a new wing under the pretense that a portion of it would be used for Black nurses and interns. The money was spent, but the hospital did not staff the wards as promised. Every year that passed (until 1942 when Dr. Harvey Middleton was allowed to join the hospital staff) meant that Black physicians could not fully practice their profession; every year that passed without Black nurses on the City Hospital wards (until 1940 when Easter Goodnight was employed) denied Black women the financial advantage of a good salary and respected professional opportunities. Every year that passed without African Americans receiving treatment from providers who they trusted expanded the gap that prevented them engaging adequate care.

So, you see, it’s not just about Tuskegee.